Sante Fe – Without Make Up

I love the Southwest and I love New Mexico. I have visited Sante Fe about twice a year for the past five years. I call her “My home away from home”. I am a tourist and a photographer. Each time I visit Sante Fe, I see her more for what she is. Like any beautiful woman she has many sides, many looks and, as one would expect, there is more to her than first meets the eye. At her best, she is beautiful adobe architecture adorned with Native American and Spanish artwork. She is decked out in silver and turquoise. She is a lovely and quaint historic section with a square in the middle of town. She is of Native American, Spanish and Anglo blood.

It was on one of my first visits that I began to sense an uneasy undercurrent. I visited the IAIA Museum of Contemporary Native Arts. It is an excellent museum a block from the square. There is a wonderful gift shop with books on every aspect of Native American history. So, as I paid my entrance fee, I expected to see more of the beautiful Native American artwork which adorned the walls of my hotel, across the street. I entered the gallery and was immediately brought down to earth. There, as one of the first exhibits, was a life-sized wooden dog with nails hammered all over its body, symbolizing how Native Americans feel they have been treated. I looked on the walls. Each piece of art depicted Native Americans being abused, killed and tortured by “Americans”, as white Europeans were depicted there. There were pictures of U.S. Air Force planes dropping bombs on American Indians.

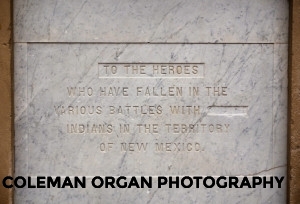

I left the gallery in an aggravated state. “How dare those Indians spoil my vacation”. And, whether I liked it or not, I was being shown another side of Sante Fe. And, she has revealed that side more on each of my visits. After the museum I looked at the obelisk, a stone pillar in the middle of the square. One of its four plaques is dedicated to those “heros” who have fallen in the various battles with indians in the territory of New Mexico. As you can see from the attached image, a word has been carved out of the marble with a chisel. And it is when I photographed this that I began to be a “photographer”. I define a photographer as one who “sees”.

When I Googled what the wording was before the obvious surgery I found it was “savage”. The plaque and its defacement was a palpable sign of anger and resentment felt by Native Americans. And, that resentment was clearly simmering in the background at my beautiful vacation spot. It was time to wake up, albeit painfully.

I have since learned to look, to “see” with more than rose colored glasses. Seeing is paying attention with more than a camera. It is learning about a place and feeling its undercurrents. It is learning to care for its people or, at a minimum, to understand them. So, I began to look for other “signs” of what I felt viscerally. I talked to a number of the Native Americans who I met in shops I have frequented over the years. I did not discover any deep animosity there. Native Americans I have met are, by and large, a very quiet people and are not preoccupied with the battles depicted on the walls of the Museum.

But I kept looking. I found other signs, literally. On my last visit, I walked out of the museum only to see this painted on the side of the postal drop box, thirty feet from the door. The sign of a young Indian whose portrait is atop paint streaming down over the “United States Postal Service” logo, could not be more direct in its message, particularly considering the location of the image. I kept looking and found another “sign”. This one was on the back side of a building about a block from the square and no more than 100 feet from my hotel, one of the nicest in Sante Fe.

And so, I was learning to look deeper, to understand her more. That is the gift of photography if we will let her teach us.

I visited a bookstore nearby and browsed the many titles which focused on New Mexico and the Sante Fe area. I came on one called The Myth of Sante Fe by Chris Wilson. He writes, essentially, that Sante Fe is a tourist resort, built to be as much, from the ground up and at the behest of the early city fathers. The ubiquitous adobe in town is, according to Wilson, not a truly natural historical development but simply mandated by the city’s government to bring in the tourists. And I will admit to you that, “Frankly, my dear, I don’t give a damn.” I love her anyway. She has given me much and taught me to “see” and to “care”, as she is still my “home away from home”, a place I want to be.